- Home

- André Naffis-Sahely

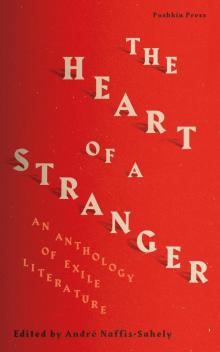

The Heart of a Stranger Page 17

The Heart of a Stranger Read online

Page 17

CARD NO. 512210

Bisbee

We are waiting, brother, waiting

Tho’ the night be dark and long

And we know ’tis in the making

Wondrous day of vanished wrongs.

They have herded us like cattle

Torn us from our homes and wives.

Yes, we’ve heard their rifles rattle

And have feared for our lives.

We have seen the workers, thousands,

Marched like bandits, down the street

Corporation gunmen round them

Yes, we’ve heard their tramping feet.

It was in the morning early

Of that fatal July 12th

And the year nineteen seventeen

This took place of which I tell.

Servants of the damned bourgeois

With white bands upon their arms

Drove and dragged us out with curses,

Threats, to kill on every hand.

Question, protest all were useless

To those hounds of hell let loose.

Nothing but an armed resistance

Would avail with these brutes.

There they held us, long lines weary waiting

’Neath the blazing desert sun.

Some with eyes bloodshot and bleary

Wished for water, but had none.

Yes, some brave wives brought us water

Loving hands and hearts were theirs.

But the gunmen, cursing often,

Poured it out upon the sands.

Down the streets in squads of fifty

We were marched, and some were chained,

Down to where shining rails

Stretched across the sandy plains.

Then in haste with kicks and curses

We were herded into cars

And it seemed our lungs were bursting

With the odor of the Yards.

Floors were inches deep in refuse

Left there from the Western herds.

Good enough for miners. Damn them.

May they soon be food for birds.

No farewells were then allowed us

Wives and babes were left behind,

Tho I saw their arms around us

As I closed my eyes and wept.

After what seemed weeks of torture

We were at our journey’s end.

Left to starve upon the border

Almost on Carranza’s land.

Then they rant of law and order,

Love of God, and fellow man,

Rave of freedom o’er the border

Being sent from promised lands.

Comes the day, ah! we’ll remember

Sure as death relentless, too,

Grim-lipped toilers, their accusers

Let them call on God, not on you.

EMMA GOLDMAN

from Living My Life

Saturday, December 20 was a hectic day, with vague indications that it might be our last. We had been assured by the Ellis Island authorities that we were not likely to be sent away before Christmas, certainly not for several days to come. Meanwhile we were photographed, finger-printed, and tabulated like convicted criminals. The day was filled with visits from numerous friends who came individually and in groups. Self-evidently, reporters also did not fail to honour us. Did we know when we were going, and where? And what were my plans about Russia? “I will organize a Society of Russian Friends of American Freedom,” I told them. “The American Friends of Russia have done much to help liberate that country. It is now the turn of free Russia to come to the aid of America.”

Harry Weinberger was still very hopeful and full of fight. He would soon get me back to America, he insisted, and I should keep myself ready for it. Bob Minor smiled incredulously. He was greatly moved by our approaching departure; we had fought together in many battles and he was fond of me. Sasha he literally idolized and he felt his deportation as a severe personal loss. The pain of separation from Fitzi was somewhat mitigated by her decision to join us in Soviet Russia at the first opportunity. Our visitors were about to leave when Weinberger was officially notified that we were to remain on the island for several more days. We were glad of it and we arranged with our friends to come again, perhaps for the last time, on Monday, no callers being allowed on the island on the Lord’s day.

I returned to the pen I was sharing with my two girl comrades. The State charge of criminal anarchy against Ethel had been withdrawn, but she was to be deported just the same. She had been brought to America as a child; her entire family were in the country, as well as the man she loved, Samuel Lipman, sentenced to twenty years at Leavenworth. She had no affiliations in Russia and was unfamiliar with its language. But she was cheerful, saying that she had good cause to be proud: she was barely eighteen, yet she had already succeeded in making the powerful United States Government afraid of her.

Dora Lipkin’s mother and sisters lived in Chicago. They were working people too poor to afford a trip to New York, and the girl knew that she would have to leave without even bidding her loved ones good-bye. Like Ethel, she had been in the country for a long time, slaving in factories and adding to the country’s wealth. Now she was being kicked out, but fortunately her lover was also among the men to be deported.

I had not met either of the girls before, but our two weeks on Ellis Island had established a strong bond between us. This evening my room-mates again kept watch while I was hurriedly answering important mail and penning my last farewell to our people. It was almost midnight when suddenly I caught the sound of approaching footsteps. “Look out, someone’s coming!” Ethel whispered. I snatched up my papers and letters and hid them under my pillow. Then we threw ourselves on our beds, covered up, and pretended to be asleep.

The steps halted at our room. There came the rattling of keys; the door was unlocked and noisily thrown open. Two guards and a matron entered. “Get up now,” they commanded, “get your things ready!” The girls grew nervous. Ethel was shaking as in fever and helplessly rummaging among her bags. The guards became impatient. “Hurry, there! Hurry!” they ordered roughly. I could not restrain my indignation. “Leave us so we can get dressed!” I demanded. They walked out, the door remaining ajar. I was anxious about my letters. I did not want them to fall into the hands of the authorities, nor did I care to destroy them. Maybe I should find someone to entrust them to, I thought. I stuck them into the bosom of my dress and wrapped myself in a large shawl.

In a long corridor, dimly lit and unheated, we found the men deportees assembled, little Morris Becker among them. He had been delivered to the island only that afternoon with a number of other Russian boys. One of them was on crutches; another, suffering from an ulcerated stomach, had been carried from his bed in the island hospital. Sasha was busy helping the sick men pack their parcels and bundles. They had been hurried out of their cells without being allowed even time to gather up all their things. Routed from sleep at midnight, they were driven bag and baggage into the corridor. Some were still half-asleep, unable to realize what was happening.

I felt tired and cold. No chairs or benches were about, and we stood shivering in the barn-like place. The suddenness of the attack took the men by surprise and they filled the corridor with a hubbub of exclamations and questions and excited expostulations. Some had been promised a review of their cases, others were waiting to be bailed out pending final decision. They had received no notice of the nearness of their deportation and they were overwhelmed by the midnight assault. They stood helplessly about, at a loss what to do. Sasha gathered them in groups and suggested that an attempt be made to reach their relatives in the city. The men grasped desperately at that last hope and appointed him their representative and spokesman. He succeeded in prevailing upon the island commissioner to permit the men to telegraph, at their own expense, to their friends in New York for money and necessaries.

Messenger boys hurried back and forth, collecting special-delivery l

etters and wires hastily scribbled. The chance of reaching their people cheered the forlorn men. The island officials encouraged them and gathered in their messages, themselves collecting pay for delivery and assuring them that there was plenty of time to receive replies.

Hardly had the last wire been sent when the corridor filled with State and Federal detectives, officers of the Immigration Bureau and Coast Guards. I recognized Caminetti, Commissioner General of Immigration, at their head. The uniformed men stationed themselves along the walls, and then came the command: “Line up!” A sudden hush fell upon the room. “March!” It echoed through the corridor.

Deep snow lay on the ground; the air was cut by a biting wind. A row of armed civilians and soldiers stood along the road to the bank. Dimly the outlines of a barge were visible through the morning mist. One by one the deportees marched, flanked on each side by the uniformed men, curses and threats accompanying the thud of their feet on the frozen ground. When the last man had crossed the gangplank, the girls and I were ordered to follow, officers in front and in back of us.

We were led to a cabin. A large fire roared in the iron stove, filling the air with heat and fumes. We felt suffocating. There was no air nor water. Then came a violent lurch; we were on our way.

I looked at my watch. It was 4:20 A.M. on the day of our Lord, December 21, 1919. On the deck above us I could hear the men tramping up and down in the wintry blast. I felt dizzy, visioning a transport of politicals doomed to Siberia, the étape of former Russian days. Russia of the past rose before me and I saw the revolutionary martyrs being driven into exile. But no, it was New York, it was America, the land of liberty! Through the port-hole I could see the great city receding into the distance, its sky-line of buildings traceable by their rearing heads. It was my beloved city, the metropolis of the New World. It was America, indeed, America repeating the terrible scenes of tsarist Russia! I glanced up — the Statue of Liberty!

TEFFI

The Gadarene Swine

There are not many of them, of these refugees from Sovietdom. A small group of people with nothing in common; a small motley herd huddled by the cliff’s edge before the final leap. Creatures of different breeds and with coats of different colours, entirely alien to one another, with natures that have perhaps always been mutually antagonistic, they have wandered off together and collectively refer to themselves as “we”. They have wandered off for no purpose, for no reason. Why?

The legend of the country of the Gadarenes comes to mind. Men possessed by demons came out from among the tombs, and Christ healed them by driving the demons into a herd of swine, and the swine plunged from a cliff and drowned.

Herds of a single animal are rare in the East. More often they are mixed. And in the herd of Gadarene swine there were evidently some meek, frightened sheep. Seeing the crazed swine hurtling along, these sheep took to their heels too.

“Is that our lot?”

“Yes, they’re running for it!”

And the meek sheep plunged down after the swine and they all perished together.

Had dialogue been possible in the course of this mad dash, it might have resembled what we’ve been hearing so often in recent days:

“Why are we running?” ask the meek.

“Everyone’s running.”

“Where are we running to?”

“Wherever everyone else is running.”

“What are we doing with them? They’re not our kind of people. We shouldn’t be here with them. Maybe we ought to have stayed where we were. Where the men possessed by demons were coming out from the tombs. What are we doing? We’ve lost our way, we don’t know what we’re…”

But the swine running alongside them know very well what they’re doing. They egg the meek on, grunting “Culture! We’re running towards culture! We’ve got money sewn into the soles of our shoes. We’ve got diamonds stuck up our noses. Culture! Culture! Yes, we must save our culture!”

They hurtle on. Still on the run, they speculate. They buy up, they buy back, they sell on. They peddle rumours. The fleshy disc at the end of a pig’s snout may only look like a five-kopek coin, but the swine are selling them now for a hundred roubles.

“Culture! We’re saving culture! For the sake of culture!”

“How very strange!” say the meek. “‘Culture’ is our kind of word. It’s a word we use ourselves. But now it sounds all wrong. Who is it you’re running away from?”

“The Bolsheviks.”

“How very strange!” the meek say sadly. “Because we’re running away from the Bolsheviks, too.”

If the swine are fleeing the Bolsheviks, then it seems that the meek should have stayed behind.

But they’re in headlong flight. There’s no time to think anything through.

They are indeed all running away from the Bolsheviks. But the crazed swine are escaping from Bolshevik truth, from socialist principles, from equality and justice, while the meek and frightened are escaping from untruth, from Bolshevism’s black reality, from terror, injustice and violence.

“What was there for me to do back there?” asks one of the meek. “I’m a professor of international law. I could only have died of hunger.”

Indeed, what is there for a professor of international law to do — a man whose professional concern is the inviolability of principles that no longer exist? What use is he now? All he can do is give off an air of international law. And now he’s on the run. During the brief stops he hurries about, trying to find someone in need of his international law. Sometimes he even finds a bit of work and manages to give a few lectures. But then the crazed swine break loose and sweep him along behind them.

“We have to run. Everyone is running.”

Out-of-work lawyers, journalists, artists, actors and public figures — they’re all on the run.

“Maybe we should have stayed behind and fought?”

Fought? But how? Make wonderful speeches when there’s no one to hear them? Write powerful articles that there’s nowhere to publish?

“And who should we have fought against?”

Should an impassioned knight enter into combat with a windmill, then — and please remember this — the windmill will always win. Even though this certainly does not mean — and please remember this too — that the windmill is right.

They’re running. They’re in torment, full of doubt, and they’re on the run.

Alongside them, grunting and snorting and not doubting anything, are the speculators, former gendarmes, former Black Hundreds and a variety of other former scoundrels. Former though they may be, these groups retain their particularities.

There are heroic natures who stride joyfully and passionately through blood and fire towards — ta-rum-pum-pum! — a new life!

And there are tender natures who are willing, with no less joy and no less passion, to sacrifice their lives for what is most wonderful and unique, but without the ta-rum-pum-pum. With a prayer rather than a drum roll.

Wild screams and bloodshed extinguish all light and colour from their souls. Their energy fades and their resources vanish. The rivulet of blood glimpsed in the morning at the gates of the commissariat, a rivulet creeping slowly across the pavement, cuts across the road of life for ever. It’s impossible to step over it.

It’s impossible to go any further. Impossible to do anything but turn and run.

And so these tender natures run.

The rivulet of blood has cut them off for ever, and they shall never return.

Then there are the more everyday people, those who are neither good nor bad but entirely average, the all-too-real people who make up the bulk of what we call humanity. The ones for whom science and art, comfort and culture, religion and laws were created. Neither heroes nor scoundrels — in a word, just plain, ordinary people.

To exist without the everyday, to hang in the air without any familiar footing — with no sure, firm earthly footing — is something only heroes and madmen can do.

A “normal person” ne

eds the trappings of life, life’s earthly flesh — that is, the everyday.

Where there’s no religion, no law, no conventions, no settled routine (even if only the routine of a prison or a penal camp), an ordinary, everyday person cannot exist.

At first he’ll try to adapt. Deprived of his breakfast roll, he’ll eat bread; deprived of bread, he’ll settle for husks full of grit; deprived of husks, he’ll eat rotten herring — but he’ll eat all of this with the same look on his face and the same attitude as if he were eating his usual breakfast roll.

But what if there’s nothing to eat at all? He loses his way, his light fades, the colours of life turn pale for him.

Now and then there’s a brief flicker from some tremulous beam of light.

“Apparently they take bribes too! Did you know? Have you heard?”

The happy news takes wing, travelling by word of mouth — a promise of life, like “Christ is Risen!”

Bribery! The everyday, the routine, a way of life we know as our own! Something earthly and solid!

But bribery alone does not allow you to settle down and thrive.

You must run. In pursuit of your daily bread in the biblical sense of the word: food, clothing, shelter, and labour that provides these things and law that protects them.

Children must acquire the knowledge needed for work, and people of mature years must apply this knowledge to the business of everyday life.

So it has always been, and it cannot of course be otherwise.

There are heady days in the history of nations — days that have to be lived through, but that one can’t go on living in for ever.

“Enough carousing — time to get down to work.”

Does this mean, then, that we have to do things in some new way? What time should we go to work? What time should we have lunch? Which school should we prepare the children for? We’re ordinary people, the levers, belts, screws, wheels and drives of a vast machine, we’re the core, the very thick of humanity — what do you want us to do?

The Heart of a Stranger

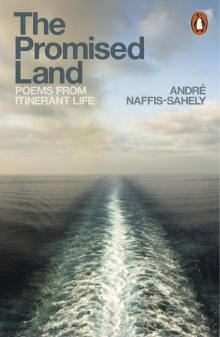

The Heart of a Stranger The Promised Land

The Promised Land